I was in high school when JK Rowling wrote Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Perhaps I thought I was too old to read a kid’s book. Or maybe I was too distracted by sports and friends to care about the intense controversy burning in evangelical circles. Harry Potter was a wizard and used magic!

I was vaguely aware, however, of a contradiction that found its way into many arguments against the books. If Christians shouldn’t read Harry Potter or any other books filled with magic, then why do many parents who oppose Harry Potter nearly universally accept books like The Chronicles of Narnia and movies like The Wizard of Oz? Are we at liberty to pick and choose which magic is acceptable and which is not?

It wasn’t until college that I finally watched the Harry Potter movies. I was at a friend’s house when I saw Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone sitting on the DVD shelf. I popped the movie in and was hooked. Soon Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets followed and then Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. After this I read the book series.

Harry Potter had everything I liked in a good story: adventure, comedy, mystery, romance, courage, friendship, imagination, good vs evil, excitement, and perhaps most all, wonder. JK Rowling is a true master of the craft.

But what to do with the magic? Should Christians read Harry Potter?

It’s been years since the controversy brewed, although Catholic priests in Poland recently condemned Harry Potter with a good old-fashioned book burning. But the topic came up recently at Sunny’s Cafe, a favorite haunt of mine and my two cousins, Garrett and Sterling, during one of our customary Saturday morning breakfasts – I like to think of Sunny’s as our own version of The Eagle and Child.

Following this debate, I developed the desire to write out my thoughts in full. This article is the consummation of that desire.

Common Ground

Let me begin by establishing an area of common ground on which I believe we all agree: God forbids Christians to practice magic. This is explicitly stated in the Bible and is, as far as I know, uncontested. We shall leave it there.

Yet even as we read Scripture, we see men of God performing supernatural acts that can only be described as…magical. Aaron casts down his staff on the ground before Pharoah, turning it into a serpent. Moses parts the Red Sea! Joshua stops the earth’s rotation!

Isn’t that magic? Certainly, turning your walking staff into a snake sounds a lot like something out of a Harry Potter novel – indeed, the serpent is a sign of many dark wizards. But not even the most ardent Harry Potter critic would accuse Aaron and the other biblical figures of anything nefarious. Why not? The answer is obvious and simple: God gave all those men the power to perform great deeds; therefore, it cannot be evil.

I think we can draw an important conclusion from this. God opposes magic, certainly; but He does not oppose all supernatural power. In fact, He often grants supernatural power to men and women for specific purposes. What God opposes is the natural man obtaining and using supernatural power that is not from God. This is always evil because there is only one other supernatural source outside of God’s own: the demonic.

Magic vs Miracle

One of the common complaints about Harry Potter is that both “good” and “evil” wizards use the same spells. But look closer at the example of Aaron and the serpent.

Then the Lord said to Moses and Aaron, “When Pharaoh says to you, ‘Prove yourselves by working a miracle,’ then you shall say to Aaron, ‘Take your staff and cast it down before Pharaoh, that it may become a serpent.’” So Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh and did just as the Lord commanded. Aaron cast down his staff before Pharaoh and his servants, and it became a serpent. Then Pharaoh summoned the wise men and the sorcerers, and they, the magicians of Egypt, also did the same by their secret arts. For each man cast down his staff, and they became serpents. – Exodus 7:8-12A (ESV)

Both Aaron and the Pharoah’s magicians turned their staffs into serpents. But there is one significant distinction provided by Scripture and it is the distinction: Aaron’s power came from God whereas the magicians’ power came from “their secret arts” – presumably demonic. And, just to show Pharoah that the God of Israel was superior to his gods, verse 12 tells us “But Aaron’s staff swallowed up their staffs.”

This is crucial. The source is the fundamental distinction between what constitutes “good” supernatural power and “bad” supernatural power. In the Bible this is true 100% of the time. There are no exceptions.

When God bestows supernatural power to mortal man we call it “miracles” or “gifts of the Spirit.” When man obtains supernatural power from demonic sources we call it “magic” or “sorcery.” Again, it is the source of power that determines whether it is good or bad.

Magic in Fiction

If magic always represents evil demonic sources in the real world, what do we do about magic in fiction? This is the point where many Christian arguments falter and begin to get jumbled and tangled into an undiscernible mass, plagued (in my opinion) by two major inconsistencies.

The first inconsistency is that most Christians who are against the use of magic in books like Harry Potter have no problem with magic used in other fiction. For example, many of C.S. Lewis’ characters in The Chronicles of Narnia not only practice magic but are pagan in origin. The same is true of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Both have been put forward as Christian works of fiction.

Many of these same Christians also have no problem letting their children watch Disney movies such as The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast; most of which contain magical creatures, wizards, and the like. What makes these works of fiction exempt from the biblical mandate on magic?

They would answer that magic in “acceptable” fiction is practiced by secondary or tertiary characters, not the main characters. But this answer yields our second major inconsistency.

As it happens, the main characters do practice magic. Susan, in The Chronicles of Narnia, wields a magic horn – given to her by Santa Clause no less – used to call for help in time of need. Aragorn, in Lord of the Rings, is a noted healer – healing being the sign of his kingship over Gondor – and he uses plants and herbs to heal much in the same way a tribal Shaman might heal. Prince Caspian’s half-dwarf teacher, Cornelius, is an apparent astrologer – in the manner of the Magi of the Nativity. Magic is a mainstay of certain races like elves, and that is not to mention wizards like Coriakin, Gandalf, and Radagast the Brown.

Moving outside the two pillars of “Christian” fantasy, we accept that Superman can fly and catch bullets with his teeth, The Flash runs a 100 meter dash in just under .5 seconds, and Spiderman – an unholy combination of spider and man, yuck – is about as demonic a combination as I can think of!

Why are these acceptable whereas Harry Potter is unacceptable? I believe that it boils down to three basic considerations:

- Physiognomy

- Real World vs Fictional World Constructs

- Morality in Fiction

Physiognomy

Physiognomy is the state in which outward appearance is seen as a manifestation of inward character. In other words, if someone or something looks evil or good on the outside it indicates an evil or good character respectively on the inside. In straightforward terms, we call this “appearances.” In cliché, it’s called “judging a book by its cover.”

We all do it, to one extent or another. This is why God told the prophet, Samuel, “For the Lord sees not as man sees: man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart.” (I Samuel 16:7 – ESV) The Bible also tells us that Satan “disguises himself as an angel of light.” (2 Corinthians 11:14 – ESV) and by so doing deceives us, knowing that mankind is prone to judge character by appearances. This is physiognomy.

In fiction, authors employ physiognomy to indicate who are the good guys and who are the bad guys. This, as a general rule, establishes audience expectations.

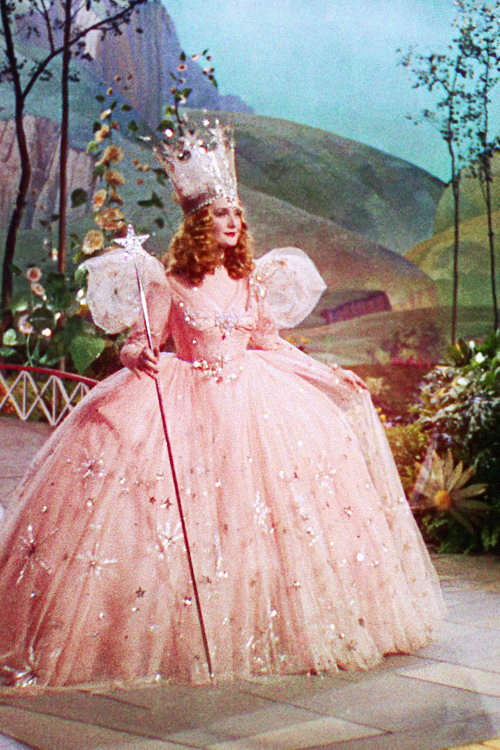

For example, consider The Wizard of Oz. In the pictures below, can you identify who is the “good” witch and who is the “bad” witch? How do you know? The answer is physiognomy. The outward appearance reveals the inner character of each witch.

So, to answer my earlier question – why are some forms of magic in fiction “acceptable” but others “unacceptable”? I believe it has to do with physiognomy, or appearances. When magic looks good then it is acceptable – Glinda helping Dorothy on her journey to Oz, for example. When magic looks bad or resembles magic in the real world it becomes unacceptable.

Real World vs Fictional World Construct

The purpose of storytelling is not to re-create a perfect image of the real world – although most fiction is set in the real world. Storytelling is predominantly about the characters and the dilemmas they face, seen through an escalating series of conflicts and resolutions which end in a final resolution of the story called the climax.

The reader, therefore, is often asked to suspend his own reality and accept the construct of the fictional world of the author’s creation. There are two important reasons for this.

First, it would be cumbersome and even impossible for the author to close all of the possible loopholes, logical flaws, and improbabilities in his fictional world.

For example, have you ever noticed that in television and film the characters always wear clean, wrinkle-free clothes – unless the setting is a coal mine or some other specific location? Is that realistic? No. But neither is it important. Think of how distracting it would be for Lieutenant Caffey in A Few Good Men to have a mustard stain on his white officer’s uniform while he’s yelling “I want the truth!” at Colonel Jessup? Reality would be a total distraction.

Second, it allows the author to focus on the actual story, which is what the audience wants in the first place. The suspending of reality for the story often enables the author to examine real-world subjects and themes in a different context.

The Witcher series, for example, examines such universal themes as racism; but does so in the context of elves and men instead of blacks and whites. This allows us to study a serious topic removed from a real-world context, which is often highly emotional and polarized.

Yet the author does not have the liberty to simply alter reality at will. He must set the reader’s expectations as to what is acceptable and what is not. This is why setting and genre are so important to the story, for they establish the parameters of reality.

Think of how you would react reading a Depression-era novel in which the beleaguered farmer suddenly develops the power to fly and the power to move a rainstorm over his drought-ridden crops? He can’t do that! It’s stupid. And we would instantly cry foul and throw the book away as rubbish.

Yet if we were watching a Marvel movie, a superhero may do just that and we would think nothing of it.

The difference in our reaction lies in our expectations of the setting and genre.

Genre

Genre helps the author because it acts as a template that the reader already understands or is already familiar with. A Fable, for example, is “a short tale to teach a moral lesson, often with animals or inanimate objects as characters.”

In Richard Scary’s The Fox and the Crow, we do not ask ourselves if crows actually eat cheese, or why the crow is wearing a bonnet and apron. It is irrelevant because we understand that this is a fable, and therefore it is the moral that is important. However, if this same crow – with bonnet and apron – appears suddenly on the bridge of the Enterprise in Star Trek: The Next Generation, we’re going to think it is completely unrealistic and reject it, even while the crew members of the Enterprise beam to some planet’s surface while traveling at Warp 9.

The reason we accept one but not the other is that Star Trek is Science Fiction. We accept that characters move from one place to the other using warp speed. It is simply part of the Science Fiction construct.

Morality in Fiction

While settings and genres establish the parameters of the story world and are malleable, the morality of the characters is less so. This is for two reasons, I believe.

First, stories are often about morality, and therefore must follow the morality of the real world on at least a basic level. This is why we often say “what is the moral of the story?”

Second, real-world constructs like gravity or stain-free clothing are not good and evil issues. It does not violate our conscience that Superman can fly without wings. However, if he steals money from a child then it does prick our consciences.

This is not to say that all characters need to be morally flawless. Fictional characters – just like their real-world counterparts – are often very flawed individuals. Which leads to the erroneous conclusion that the author is attempting to legitimize the flaw or de-stigmatize the particular sin.

In the Bible, many of God’s chosen instruments are flawed in some major way. Rahab was the prostitute of Jericho who nonetheless gave quarter to spies from Israel – lying to do so, I might add – and yet was rewarded by God for her faithfulness. King David committed adultery and then covered it up with murder. But God chose him anyway to write most of the great Psalms praising and glorifying God.

Characters aren’t made to be flawless. They represent us, the readers, in the decision-making process.

In fiction, and specifically in fantasy, magic is rarely the moral of the story.

Ever since J.R.R. Tolkien’s seminal work of fantasy, The Lord of the Rings, magic has become a permanent part of the construct of the fantasy genre. It bears little resemblance to the kind of magic outlawed by Scripture – a.k.a the obtaining of supernatural power from demonic sources.

Source, in fantasy, is rarely discussed. The difference nearly always comes in how each person uses their magical abilities. Actions determine morality in fantasy, not source. And that makes all the difference in the world.

So what do we do with the magic we find in Harry Potter and other works of fantasy fiction? To me, the answer is clear: magic is not the magic or sorcery which God condemns in Scripture. Instead, it refers to supernatural power that is part of the very fabric of fantasy fiction.

But I do not encourage anyone to violate their conscious or simply accept my word for it. Search the Scriptures for yourself and be sure of your own conclusions. My hope is, whether you are for or against, that by reading this article you have been challenged and edified.